Over 60 and online

Over 60 and online

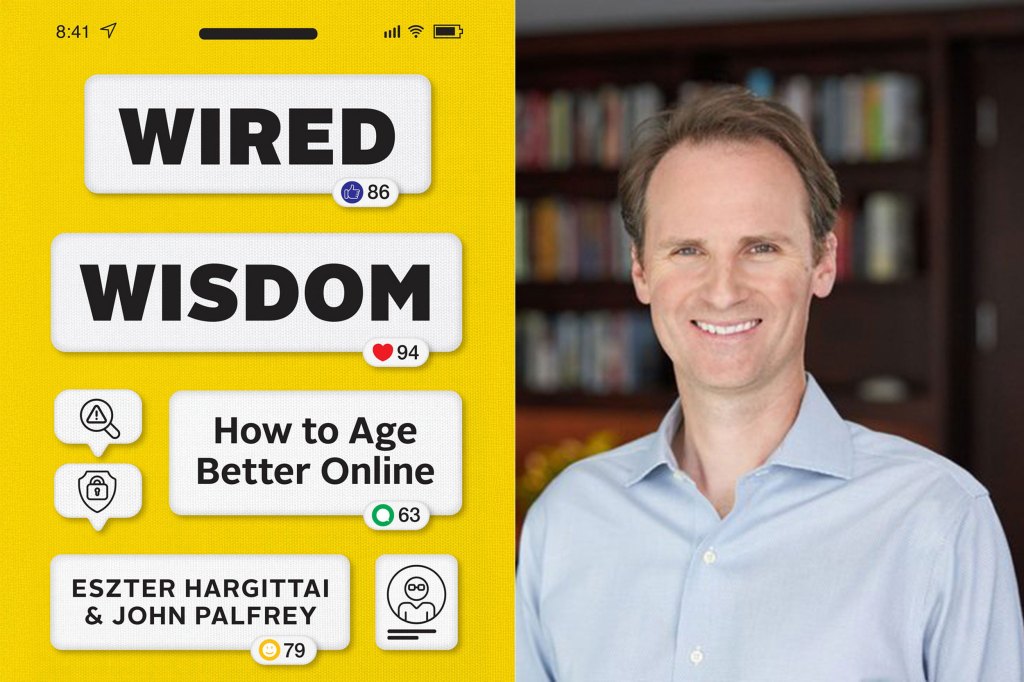

In new book, law professor busts myths about ‘hapless grandparents’ in the digital age

The fastest-growing demographic of internet users is people age 60 and older, but the group’s behavior online is poorly understood — and often stereotyped.

That’s according to John Palfrey, former executive director of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society and a visiting professor at Harvard Law School.

In a new book called “Wired Wisdom: How to Age Better Online,” co-authored with the University of Zurich’s Eszter Hargittai, Palfrey busts common myths about how older adults relate to privacy, security, and connection in the digital age.

“Too often we have the image in our mind of a hapless grandparent or older person in our life who can’t turn on the new phone they’ve received or they can’t fix the blinking light on the VCR,” said Palfrey, who is now the president of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. “What we really wanted to do with this book is help make sure that the use of technology is actually a part of thriving in older age, and not something that’s a hardship for older people.”

In this interview with the Gazette, which has been edited for length and clarity, Palfrey explains what we get wrong about the online lives of over-60s, and what can be done to support older users of new tech.

What made you want to write about older adults’ online lives?

When I was at the Berkman Klein Center in the aughts, the early days of the internet, I co-wrote a book with Urs Gasser, “Born Digital: How Children Grow Up in a Digital Age.” I had two very small kids at the time, and there were real concerns about how kids use technology. I was thinking through, how do you raise kids in this time?

This book came about in a similar way. I have parents who are both roughly 80. They’re both wonderful and brilliant people, and sometimes technology is their friend, and sometimes it’s not. I thought, how do I engage as a middle-aged person in supporting older adults? What do the data tell us about the most useful things to do?

The book draws on external data, but you also contribute a new survey of 4,000 adults over 60. What stuck out to you from that research?

Many of the myths we hold are not entirely true, and I’ll give you one example that has to do with safety and security. We think about older people as totally helpless in that they’re constantly being scammed and so forth. But it turns out, when you dig into the data, that’s not the case. Older adults are more skeptical than younger people about scams, not less. In fact, they’re able to use their history and their life experience in a very positive way to apply themselves to these online scams.

What’s going on in the data is that older people are targeted way more than younger people. Why? Because they likely have more money, they may be less good with the technology itself, and sometimes they’re suffering from cognitive decline.

So the truth is not that older adults are completely helpless against scams. It’s that they’re facing way worse conditions, and we don’t give them the same kind of training and support that we give younger people. And some of them are sitting ducks as a result.

If we treat older adults like they don’t know anything, that’s not a very good starting point for figuring out the right interventions, whether it’s changing the design of the technology, creating new laws, or intervening as family members.

“Older adults are more skeptical than younger people about scams, not less. ”

But you did find some real differences between the generations in terms of online privacy: Older adults tend to be much more skeptical about sharing personal information, whether that’s on social media or through medical alert systems that could be lifesaving. What advice do you have for navigating those conversations?

That’s right. For younger generations, everything in their life has been recorded, from their sonogram when their parent was pregnant to their baby pictures to their Little League games, and all of that is stored digitally. That’s just not true for their grandparents. There’s a big distinction coming in, and in their final chapters, older adults are having to grapple with that.

For me, that means we really shouldn’t assume too much about what people know about technology or what they will intuit, especially if they’ve been out of the workforce for a long time. They might not know how much data about them is being held by other people.

So is it really about talking to the older adults in your life and figuring out their specific needs and concerns?

Yes, I think so. This is one of the challenges: There’s a huge diversity within this age cohort, which shouldn’t be that surprising. At the MacArthur Foundation, where I work now, we have people in their 70s who do quarterly cybersecurity trainings — who are teaching the cybersecurity trainings. They just know it incredibly well. And then there are people who are exactly the same age, who haven’t been in the workforce at any point in the digital era, who know absolutely nothing about this stuff, who have no context for it.

How are older adults reckoning with the contradictions of social media — that it can both connect us and isolate us, inform us and misinform us?

It’s very much a mixed bag on both. That’s the reality for kids, too, and for those of us in the middle. Too much of it can be really harmful, but a decent dose can be a part of a positive life. To give an example, if you’re an older person and you live in Europe, and you can use WhatsApp to connect with a relative in the U.S., it can be life-giving to be able to send them texts and see their face once in a while. Having a healthy dose of social media can be a part of a strong social life.

What can be done to improve things?

The most important thing we could do is design technologies with older people in mind. Have you ever heard of older people being involved in the design of a new technology at, say, Apple? I don’t think that kind of thing is at the top of mind for those designing and carrying out these technologies. Generally speaking, new technologies are designed by quite young people for other young people, and we do little thinking about the experiences of older people. It could be as simple as font size.

We also focus on support. Great benefits can come from a grandchild connecting with their grandparent through the use of technology, helping them navigate that. The child can help the grandparent, but you also never know what skills and insights might go in the other direction. The grandchild is going to learn a whole pile of stuff from the grandparent in the process.

I really hope that as a society we focus more on treating our older adults better, really centering them in ways we don’t always today. You’ll hear people say that when we center people with disabilities in the way we build cities and buildings, we end up improving things for everybody. The same is going to be true for technology design: It’s going to become more universal as we design for older people. Particularly as artificial intelligence becomes more and more central, we urgently need to pay attention to how that’s going to affect the older population. We’ll benefit in untold ways if we do so.

Latest Harvard

- Looks like a book. Reads, to some, like a threat.Houghton exhibit explores forbidden history

- Her science writing is not for the squeamishIt takes a lot to gross out ‘Replaceable You’ author Mary Roach

- ‘How old are you? 70s? You’re JV, maybe next year.’Olympic gold winner Bill Becklean has been at crew for 75 years, will be coxing boat of octogenarians at Head of the Charles

- Harvard reports operating deficit amid federal funding cutsUniversity continues to advance teaching and research in face of significant financial challenges

- Was ‘Aeneid’ critiquing or glorifying empire?Authors of new translation dig into lasting impact of epic that Virgil wanted burned

- When your English teacher writes a book on Taylor SwiftProfessor Stephanie Burt examines star’s influence, work ethic, why her music matters