Live fast, die young, inspire Shakespeare

Live fast, die young, inspire Shakespeare

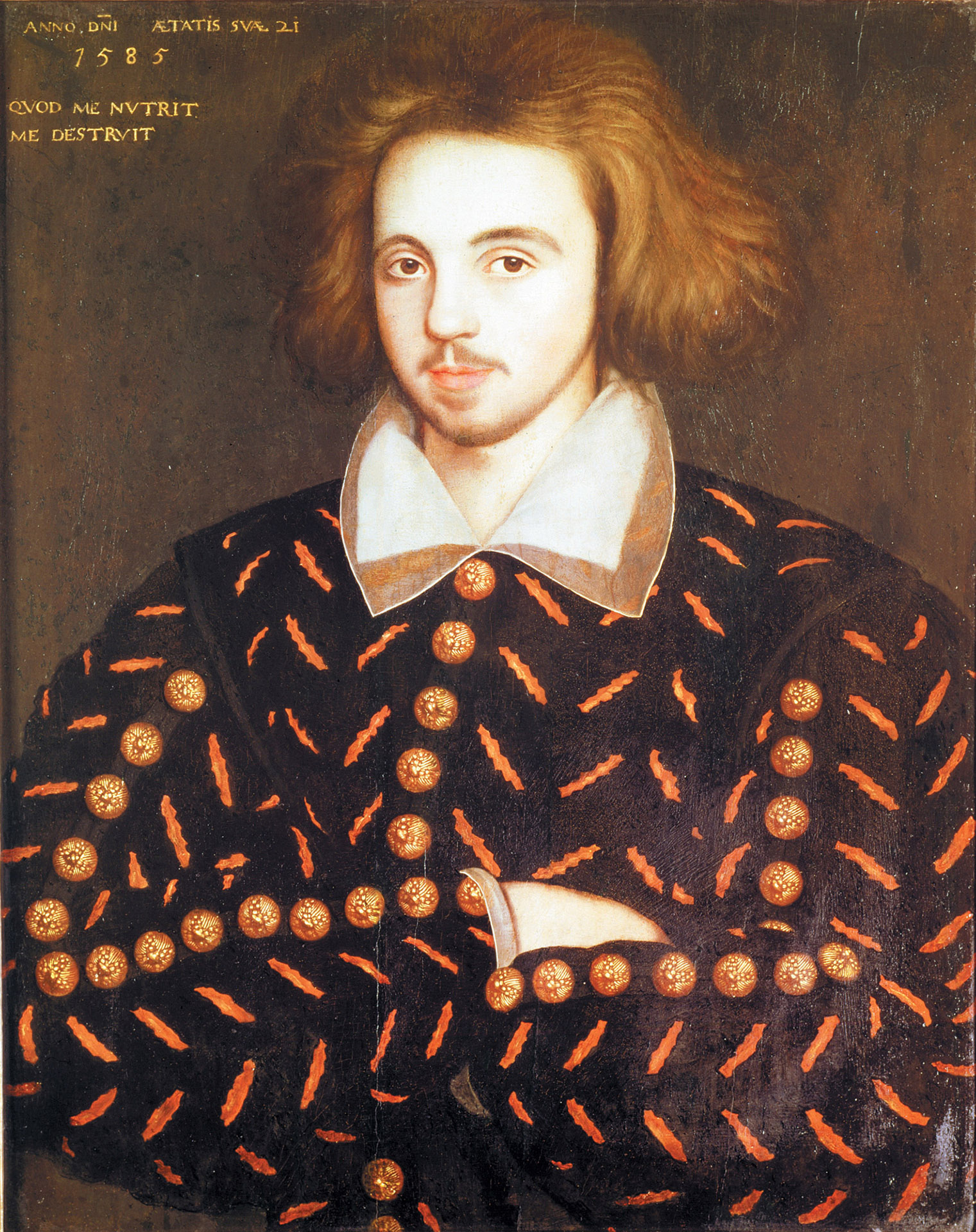

Stephen Greenblatt finds a tragic strain in the life and work of Christopher Marlowe

Many years ago, Stephen Greenblatt tried to convince the writing team behind “Shakespeare in Love” that they were chasing the wrong Renaissance playwright — that the life of Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare’s contemporary and rival, would make a better movie.

Decades later, Greenblatt has made his case with “Dark Renaissance,” a literary history of the knowns and unknowns of the life of Marlowe, killed at 29.

The book is not just a thrilling read — full of transgression and espionage — but also an argument for Marlowe’s literary significance: as much as anyone the inventor of the Elizabethan theater that Shakespeare would soon perfect, and for the tragic grandeur woven through his work, his own meteoric rise and squalid, murky death.

In an edited interview with the Gazette, Greenblatt, Cogan University Professor of the Humanities, explains what drew him irresistibly to Marlowe, and what Marlowe’s story can tell our time.

It’s important to set the scene. Your book offers a vivid picture of England in the 1560s and 1570s, when Marlowe — and Shakespeare — came of age. It is frankly a frightening place, with religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics, but also Protestants and more extreme Protestants. And it’s marked by violence, betrayal, and paranoia.

Yes. Society had split into warring parties, and the parties hated each other — it wasn’t just that they didn’t agree. People were getting killed. It must have been extremely difficult even to sit down with a big family at Christmas. You’d have to agree not to talk about a whole lot of issues.

And in addition to the internal divisions, which were tremendous, there were foreign armies threatening. The Spanish armada would sail in 1588, and Catholic powers on the continent were recruiting what we might call “terrorists”: training people to kill the queen.

And that atmosphere weighed on the culture. For years the English theater was either extremely crude or sort of arid and moralizing.

Well, yes: You just had all of these regime changes — Henry VIII; his Catholic daughter, Mary; her Protestant sister, Elizabeth — each of which was accompanied by executions. Many people understandably decided to keep their heads down.

You have to think of it as a society rather like contemporary Iran, where there is no shared public space, where — if you are the kind of person inclined to speak out, to say things that the authorities don’t approve of — you can get in tremendous trouble.

Marlowe seems to have been that kind of person. Even in his published work, there are challenges to the divine right of kings, as in “Tamburlaine,” or to God, as in “Faustus,” along with persistent elements of gore, sadism, eroticism.

Yes. We don’t just notice now, in 2025, that these are transgressive plays — he was noticed for it, and attacked for it, immediately in his own time.

And I think Marlowe would be interesting even if he was just a kind of troublemaker, or a wild freethinker in a time when that was dangerous. But what makes his story so compelling is that he was also an incredible genius. He wrote arguably the most beloved love poem of his time — “Come live with me and be my love,” everyone was singing it. Or “Hero and Leander,” a great, sexy poem. And theatrical blank verse: In “Tamburlaine,” Marlowe basically invented this astonishing new medium.

The meter, the form used by Shakespeare — who then eclipses him.

Who eclipses everyone. Shakespeare was the far greater artist, ultimately. People at the time understood that it was horrible to be imitated by Shakespeare: He would watch, absorb, digest, transform, and do what you do even better. Robert Greene, another contemporary writer, said of him, “This is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers.” But Shakespeare learned a ton from Marlowe — really a ton.

“People at the time understood that it was horrible to be imitated by Shakespeare: He would watch, absorb, digest, transform, and do what you do even better.”

The book is worth reading if only to see that Shakespeare didn’t spring out of nowhere: how he arose along with Thomas Kyd and Marlowe, in dialogue and competition with them. You say “Tamburlaine,” Marlowe’s first big success, sets the stage. It imagines this conqueror who comes from nothing and rolls over the kings of Asia Minor, a man who is brutal and godless and ambitious. And people loved it — Marlowe had to hurriedly write a second part.

It was just unlike anything that had come before. And that play helped get going, basically, the first mass entertainment industry in the modern world. Not the elegant private theaters that still existed in Italy, like in Vicenza, but this crazy thing — that brought together people who were exquisitely cultivated with pickpockets and whores, all in the same space together. Marlowe was the first person to figure that out.

This book is a natural companion to “Will in the World,” your 2004 narrative of Shakespeare’s creative life. Marlowe comes to seem like his dark twin.

I do see him that way. They were exact contemporaries. They came from similar backgrounds: both provincials, Marlowe the son of a cobbler, Shakespeare the son of a glovemaker. Their paths were different, but they both found their way to London, and to theater, at the same time.

For years, many scholars believed it possible that they never met each other. That always seemed to me wildly unlikely. Today, most scholars believe that in fact the two collaborated on plays, including the three parts of “Henry VI” — that they were in a writers’ room together.

You have a scene imagining what it was like in that room, and it’s sort of funny. Shakespeare ends up seeming careerist, cagey, sort of “square” next to Marlowe, who was a Cambridge graduate, a reputed atheist, an acquaintance to the biggest names in his world, and who died violently at just 29. He was also, notoriously, some kind of a spy for the Elizabethan regime — the source of much speculation.

Yes. We know that the Privy Council — really the most important people in the country — intervened to get Marlowe his master’s degree from Cambridge when it was being withheld. And what they said was that he “had done her Majesty good service and deserved to be rewarded.”

This is a world in which people are listening to each other, drawing out people’s secrets and reporting them to the authorities. I’m careful not to say what exactly Marlowe did, because I don’t know exactly what he did. We can only speculate, from his being a simple courier to something more sinister. But that “good service” letter — it’s not as if there are 500 more such letters around. I can’t think of another one. So I tend to think he wasn’t just a courier.

Let’s talk about his mysterious death. After a long day with some very unseemly associates, Marlowe was fatally stabbed in the eye, age 29, in 1593. His tablemates tell the authorities that it was a fight about the “recknynge” — the bill. You’re not convinced.

It’s just strange. Among the three people he was with was Robert Poley, a kind of career spy and one of the scariest people you could ever bump up against in the late 16th century. He got his hands in very bloody and sinister things, including the entrapment of Mary, Queen of Scots — though not just that.

And then we learn that a full account of the terrible, heretical things Marlowe was supposedly saying was copied and given to the queen. That’s unusual: She didn’t look at every accusation. And then it’s reported that the queen’s response was to “prosecute it to the full.” As usual, it’s murky — “prosecute it to the full” doesn’t mean “stab Marlowe to death in an inn.” But someone could easily have interpreted it as that kind of official encouragement.

Let’s close on that point. Christopher Marlowe, it seems to me, anticipates a familiar artistic type: the live-fast-die-young sort. If he had a kind of death wish, you could argue he almost wrote it into his greatest play, “Faustus,” about the doctor’s famous deal with the devil. In this version, Faustus gives up his soul for 24 years of boundless power.

Yes. There’s something intensely personal about Marlowe’s representation of Dr. Faustus. And it’s odd: In the deal, it isn’t the devil who proposes the 24 years. Faustus comes up with that. It’s as if some part of Marlowe was interested in the idea of knowing your end was not so far off.

So maybe Marlowe knew he couldn’t last forever. He ends up being a very moving character, given the little we know about him — and acknowledging that Shakespeare sort of left him in his dust.

Yes. And we don’t know what Marlowe might have become. If Shakespeare had died at 29, we’d have, what? “Two Gentlemen of Verona,” the Henry VI plays, and “Titus Andronicus”? It’s just not that interesting a career. Nearly all of his great work lay ahead of him, at that age.

And Shakespeare appeared to be as conscious of Marlowe as any contemporary writer. Marlowe was the only one he quoted directly in one of his plays. He watched Marlowe write “Edward II”; he wrote “Richard II.” Marlowe wrote “The Jew of Malta”; Shakespeare wrote “The Merchant of Venice.” Marlowe wrote “Tamburlaine” and he wrote “Titus Andronicus” — as if to say, “You want blood, I’ll give you blood!”

And then you’re clear about the trail Marlowe helped blaze, to popularize the theater, blend high and low sensibilities, write poetry for the stage, and maybe how to smuggle cultural critique into popular entertainment.

Yeah. Marlowe seemed to see a kind of wall built around him, in his time. He wanted to get out but there was no door, so he just took this hammer and smashed a hole in the wall — I’m putting it crudely. And then Shakespeare basically walked over his dead body, through the hole that he had made.

Latest Harvard

- Time for mandatory retirement ages for lawmakers, judges, presidents?Americans seem to mostly say yes; legal, medical scholars point to complexities of setting limits

- In dogs, as in humans, a harsh past might bare its teethEarly adversity leads to higher aggression and fearfulness in adult canines, study says

- Brief bursts of wisdomAphorism lover and historian James Geary reflects on how ancient literary art form fits into age of social media

- Flew home as Will Flintoft, returned as Rhodes ScholarApplied math concentrator to study computer science, theology with eye toward AI

- What will AI mean for humanity?Scholars from range of disciplines see red flags, possibilities ahead

- Tai Tsun Wu, 90Memorial Minute — Faculty of Arts and Sciences